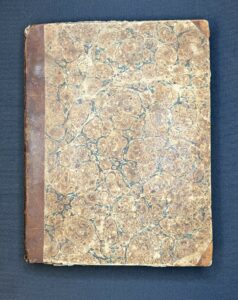

Cabinet Maker’s Notebook, 1830-1833. 2022.28.001

(Collection 2022.28)

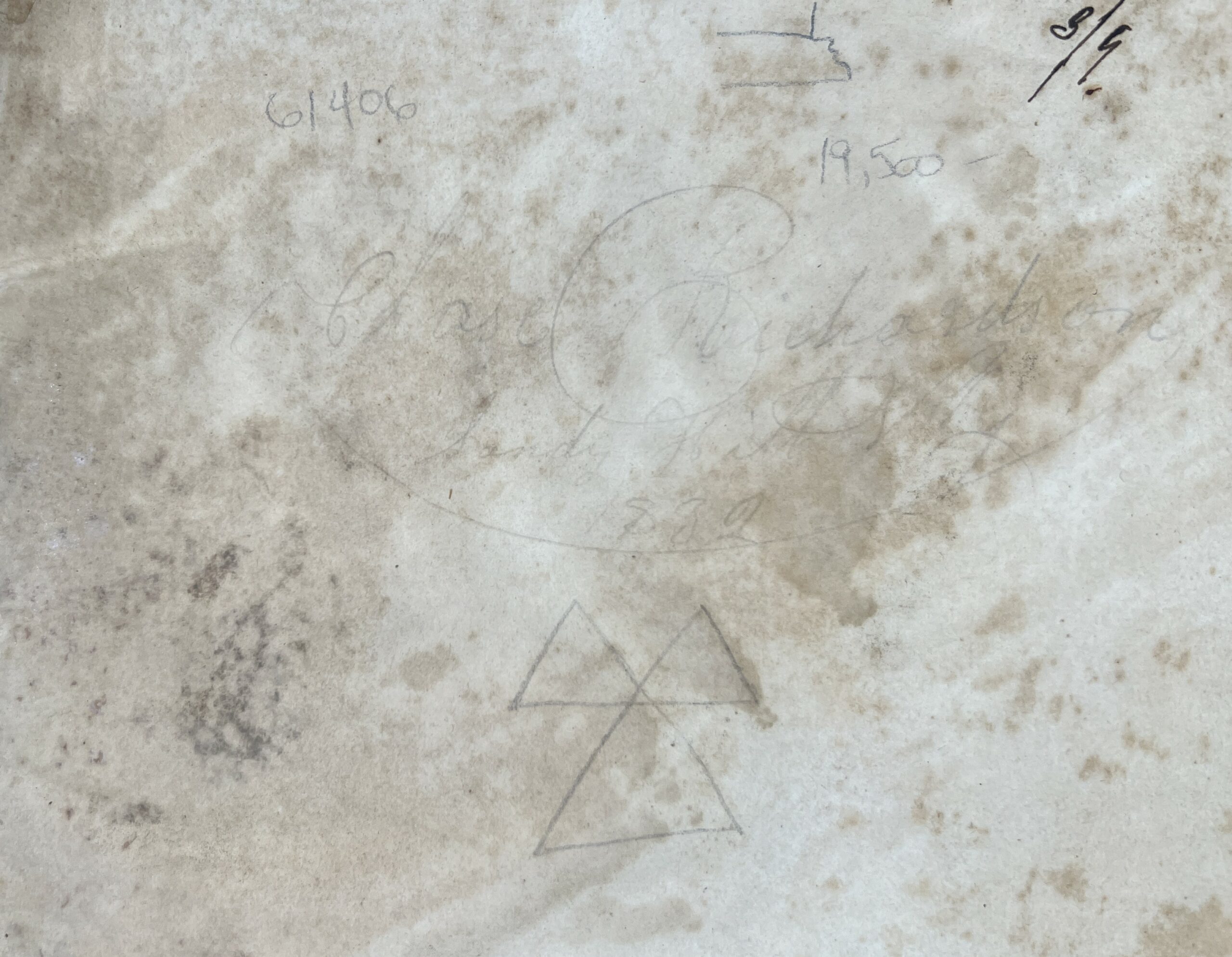

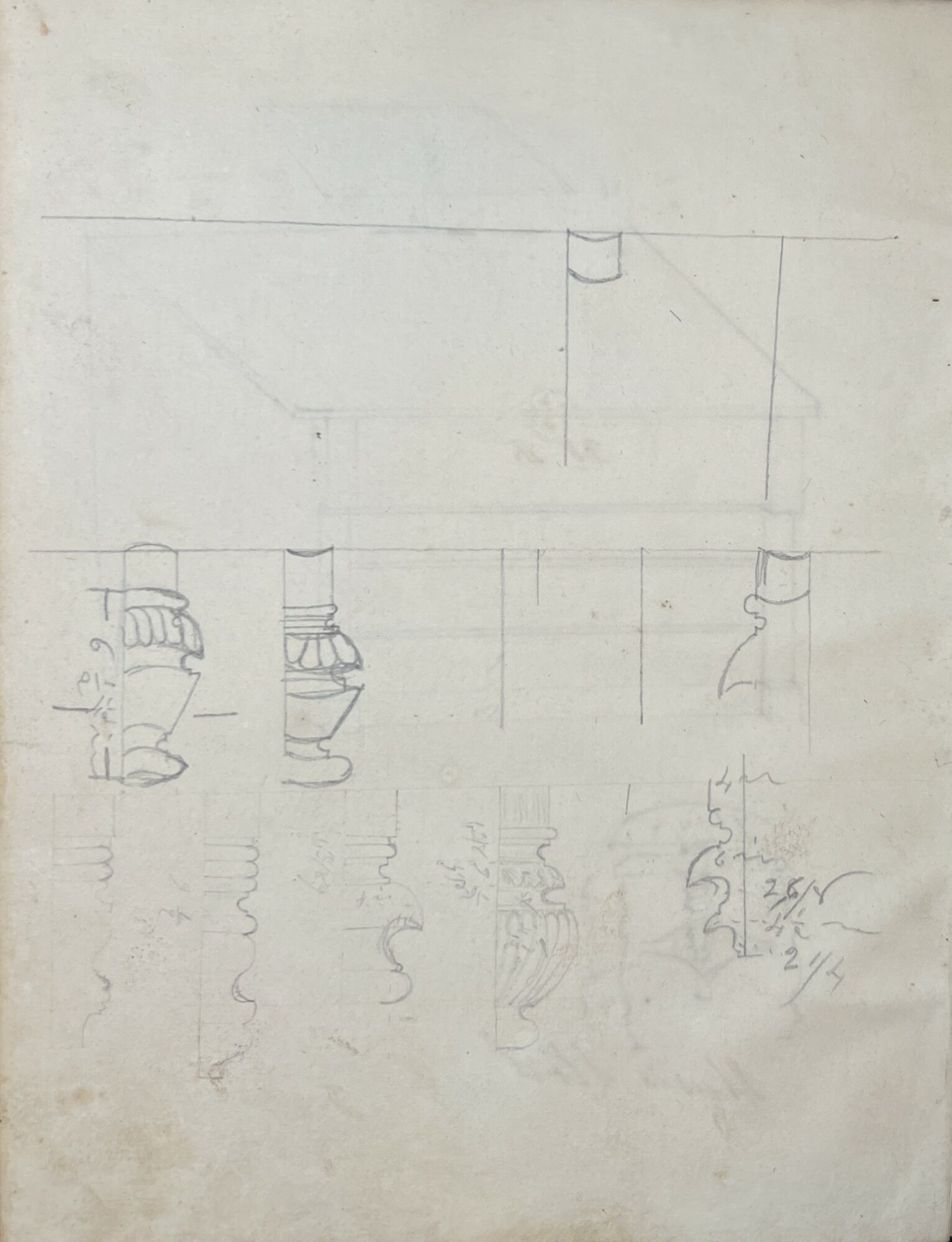

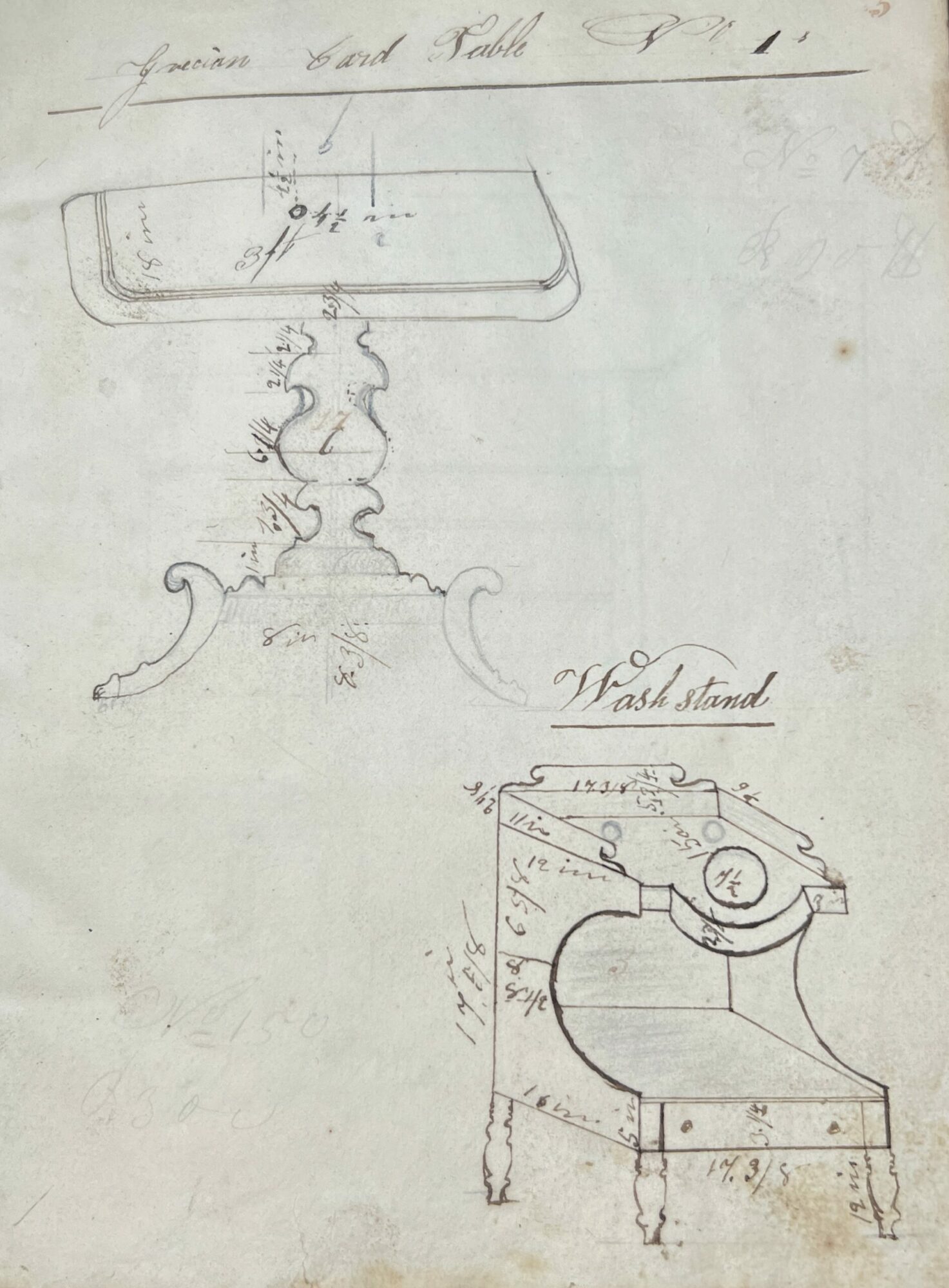

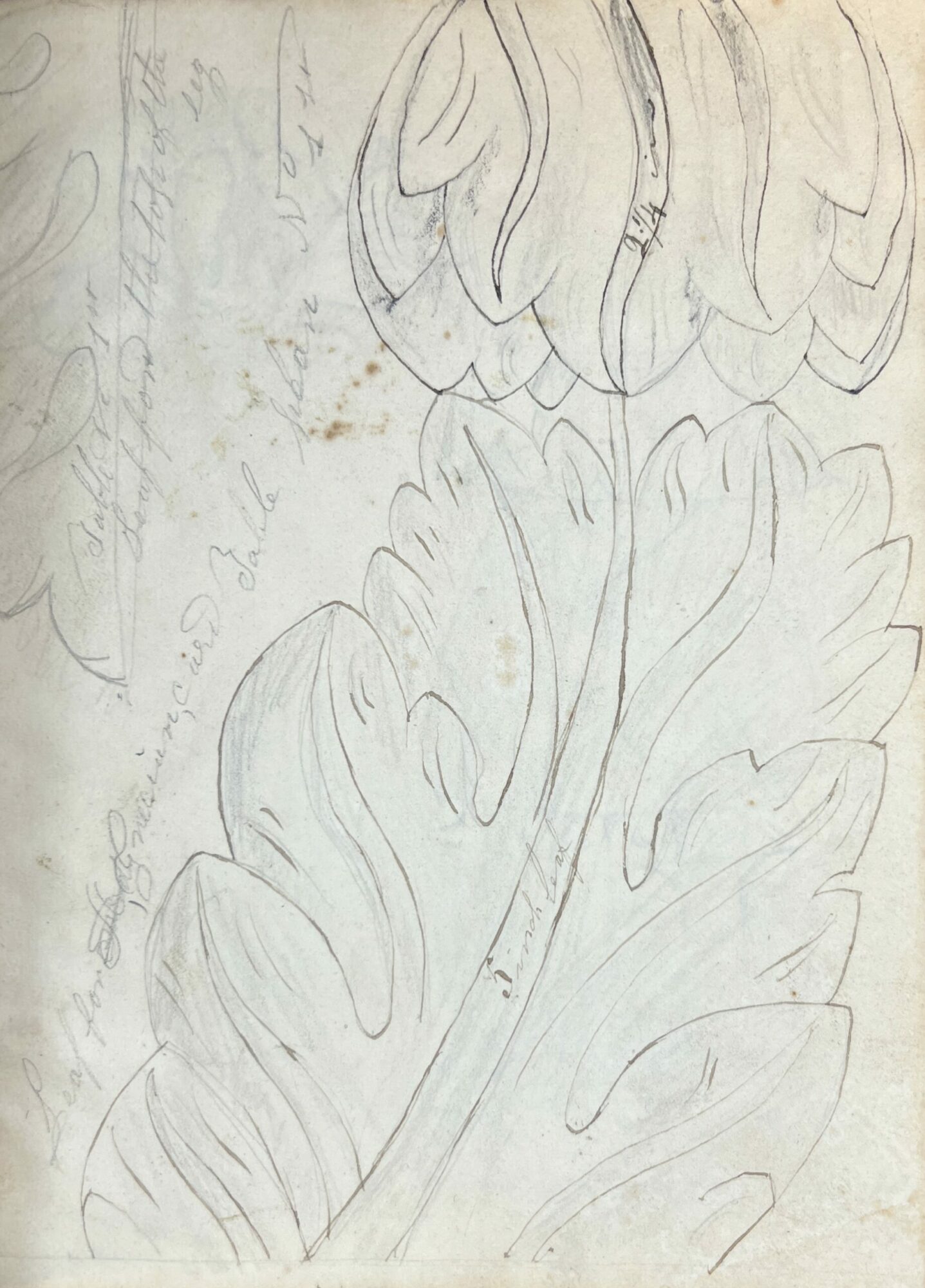

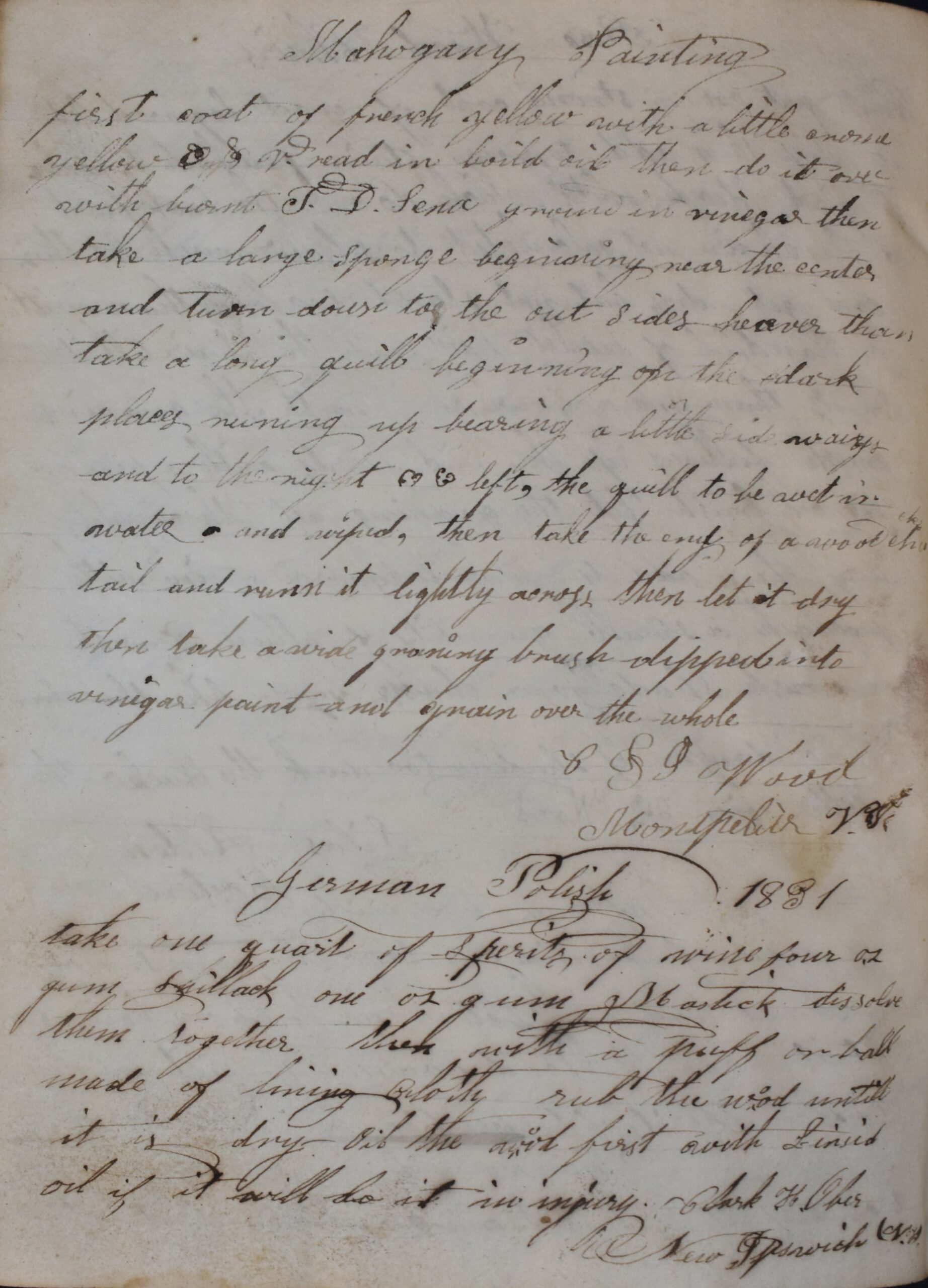

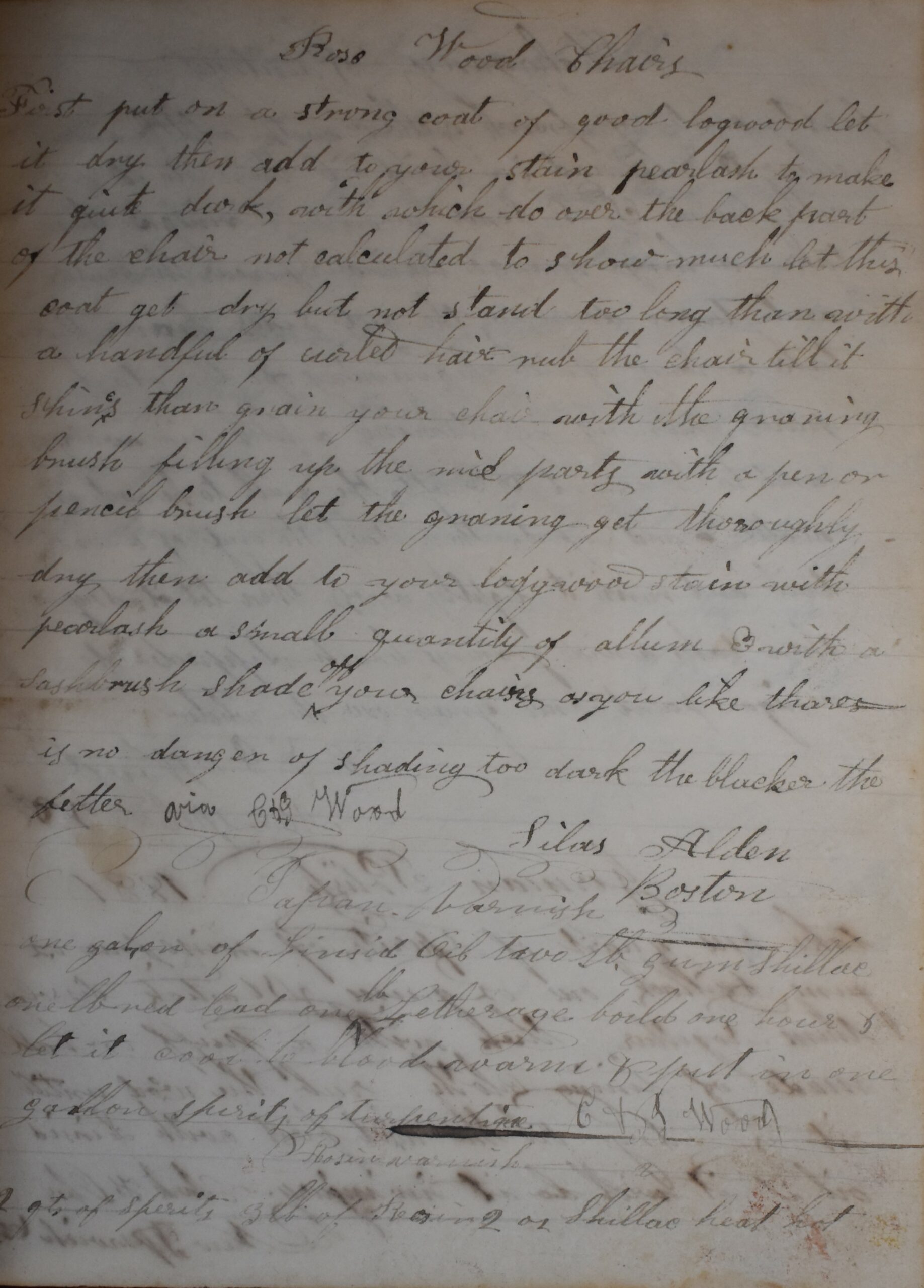

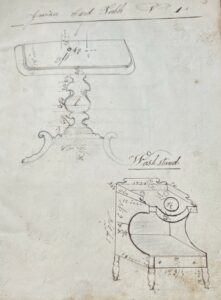

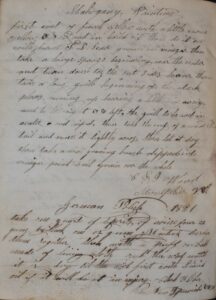

A cabinet maker’s notebook/sketchbook is quarter bound in fine brown calfskin with covers of cream, brown, and blue, marbled paper. Original binding. On the front endpaper written in light pencil it says “Chase Richardson, Sandy Hill, NY, 1832”. The inside pages are filled with drawings of various furniture rendered in both pencil and ink. Furniture is drawn with all measurements notated and most have titles stating the name of the item and the style. In some drawings different options are shown such as different styles of furniture legs and some drawings have prices listed. There are pages filled with designs of patterns that could be carved into the furniture. In the back of the notebook there are more than a dozen extremely detailed recipes for various finishes that have been attributed to the cabinet makers who created the recipe. The recipes are in different hands, possibly the creators of the recipe wrote it in his notebook for him. Various dates throughout are listed from 1830-1833.

Chase Richardson was born on August 22, 1810, in Lebanon, New Hampshire, to Jacob Chase Richardson and Eunice Fox. Jacob was the second of three children. His mother died when he was six years old, and his father married Lucy Tilden the following year. They had at least six children together and the family had moved to Vermont by 1826 as this is where their youngest son Frank was born. Based on the cabinetmaker’s notebook and a letter written by Chase Richardson in 1835,1 we know that he apprenticed or worked as a cabinetmaker in Montpelier, Vermont. Writing to fellow cabinetmaker Charles R. Wood he states, “How does all the folks do at home (at Montpellier [illegible]) it has always seemed like a home to me. How does the old shop go and & Zenas how does he do & all old friends.”2

The inscription in Chase’s notebook places him in Sandy Hill, New York, in 1832, which is just to the southwest of Montpelier, and to the north of Albany which had become a furniture making hub in the northeast. By 1835 he had settled in Holley, New York, which is to the west of Rochester, New York. The rest of his family moved to Marathon, New York, some time before 1841.3 On May 7, 1835, Chase married Phebe Cushman4 of Brockport, New York, and they settled in Holley.

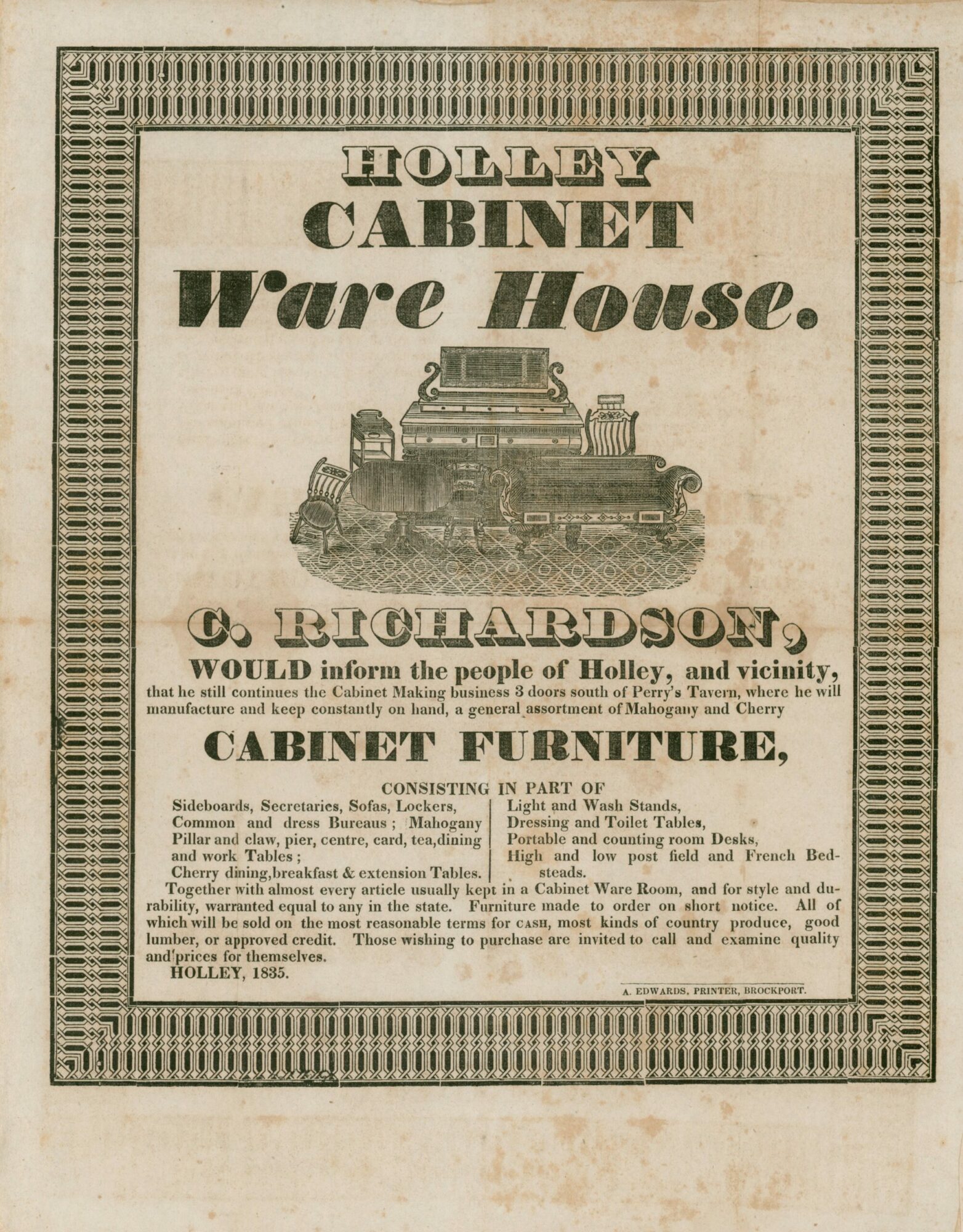

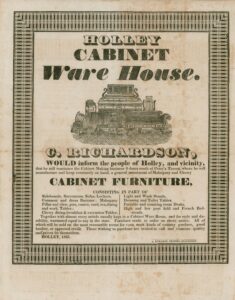

In November of 1835, he mentions in the letter he penned to Charles Wood that he had been gravely ill for “60 days” with “billious fevers” which was a term used for many maladies from malaria to typhoid. Whatever its cause, he became ill and had relapses for more than two months. He writes, “If you had seen me one week since you would knot have known me. I was nothing but a skeleton to appearance…” He then goes on to say he is feeling better and slowly getting back to work. It is around this time that he printed a broadside announcing to “the people of Holley, and the vicinity, that he still continues the Cabinet making business.” The GCV&M has this broadside in their collection as well.

Chase and Phebe had a daughter, Ellen Maria Richardson, in 1838, and Chase passed away the following year on January 19, 1839, at the age of 28. His notebook and broadside were passed down through several generations of his family. The care they took in preserving them allows us, one hundred and eighty-eight years later, to remember his life and appreciate this truly one of a kind piece of Western New York history.

In the 19th century the term “cabinetmaker” applied to a person who made all types of furniture. Learning the trade of cabinetry in the early 1800s began with an apprenticeship. It is likely that Richardson apprenticed in Vermont in the workshop of John and Cyrus Wood5 who opened their shop in Montpelier in 1816.6 Apprentices would sign contracts stating they would stay for a certain length of time. Richardson himself had apprentices once he was established although he had trouble keeping them. He writes in his 1835 letter, “while absent one day my apprentice cut stick and I have not herd from him since. This was the middle of Sep he had to stay until next April before his time was out.”7 He then goes on to lament that he had lost a previous apprentice to the chair maker who was offering them twenty-five percent more wages. Cabinetmakers relied on their apprentices as much as the apprentices relied on them to teach them the skills they needed. As a single cabinetmaker, and with being so ill, Richardson would have found staying afloat difficult. “It has been a hard pull for me. This season my boy running away as he did makes it worse if I had not been sick and my boy staid I should have called myself worth about $500 at this time.”

The location of the cabinetmakers shop would have been a strategic decision. The Wood’s workshop in Montpelier was an ideal place to set up a cabinetmaking business as it was in the ideal position to have access to local timber and waterways would have allowed easy access to the lumber. “Their prominence in that location was the result of two bounties of nature. The first is the abundance of certain varieties of timber…the second is the many tributaries of the White River” which allowed for lumber mills to flourish.8 According to his journal Richardson was in Sandy Hill, New York, in 1832. This would have been an advantageous place for him for similar reasons. Location of course, Sandy Hill was just above Albany which had access to several kinds of local timbers and numerous waterways including the Hudson River and the newly finished Erie Canal which gave easier transportation access to both New York City and Buffalo.

However, there was another reason New York would have been ideal. In the early 1800s the furniture making trade, which had been most abundant in Philadelphia until this time, made a transition to New York as it was seen as becoming the new epicenter of the business world. “Leadership in the design and production of furniture moved from Philadelphia to New York during the Federal period. This was partly because New York, with its flourishing port, assumed leadership in many areas of trade and commerce at that time.”9 It is not known what brought Richardson to Holley, New York, but it too had access to resources and was on the Erie Canal.

The life of a cabinetmaker was usually not static. As evidenced by the notebook it was important to keep up with the most recent trends in furniture. Many of Richardson’s drawings were likely drawn from observing furniture at showcases and warehouses in larger cities. The “York Bureau” is a style from York, now the city of Toronto. He has a recipe from a cabinetmaker in Boston and we know he spent time in Montpelier. In 1830 C & J Wood stated that, “One of the firm has just returned from New York with the latest city fashions for Cabinet Furniture.”10 While it is not known who this member of the firm was, Richardson would have most certainly visited New York City at least once as it would have been the ultimate dream for any cabinetmaker of the time. And of course, he would have spent quite a bit of time in Albany when he lived there. In one of his drawings, he compares his work to that of Mead & Alvord of Albany. They were the preeminent 1830s cabinetmakers in that city. It reinforces his knowledge and attempts to keep up with the latest styles. The latter part of the 1830s saw a change in the cabinetmaker business. With the Industrial Revolution came the mass production of furniture and cabinetmakers went on the decline until by the end of the 19th century only a few well-known designers were left.

- Chase Richardson to Charles R. Wood, “Chase Richardson’s Letter to Charles R. Wood,” Findagrave, 2019, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/110871806/chase_richardson. ↩︎

- Zenas was Charles Wood’s uncle, also a cabinetmaker. ↩︎

- According to census records from 1855 and 1860 his oldest half-brother Roswell Richardson was also cabinetmaker. He lived in the area around Cortland, New York. ↩︎

- Rochester Gem, accessed March 24, 2024, http://www.libraryweb.org/~digitized/serials/gem/1835Vol.VII.pdf. ↩︎

- The letter Chase Richardson wrote in 1835, in which he reminisced about the old shop, was addressed to Charles R. Wood who was the son of Cyrus. ↩︎

- Charles A. Robinson and Kenneth Joel Zogry, Vermont Cabinetmakers & Chairmakers Before 1855, a Checklist (Shelburne, Vermont: Shelburne Museum, 1994). ↩︎

- Chase Richardson to Charles R. Wood, “Chase Richardson’s Letter to Charles R. Wood,” Findagrave, 2019, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/110871806/chase_richardson. ↩︎

- Kenneth Zogry and Philip Zea, The Best the Country Affords: Vermont Furniture, 1765-1850 (Bennington, Vermont: Bennington Museum, 1995). ↩︎

- John L. Scherer, New York Furniture: The Federal Period, 1788-1825 (Albany, New York: University of the State of New York, State Education Dept., New York State Museum, 1988). ↩︎

- Charles A. Robinson and Kenneth Joel Zogry, Vermont Cabinetmakers & Chairmakers Before 1855, a Checklist (Shelburne, Vermont: Shelburne Museum, 1994). ↩︎