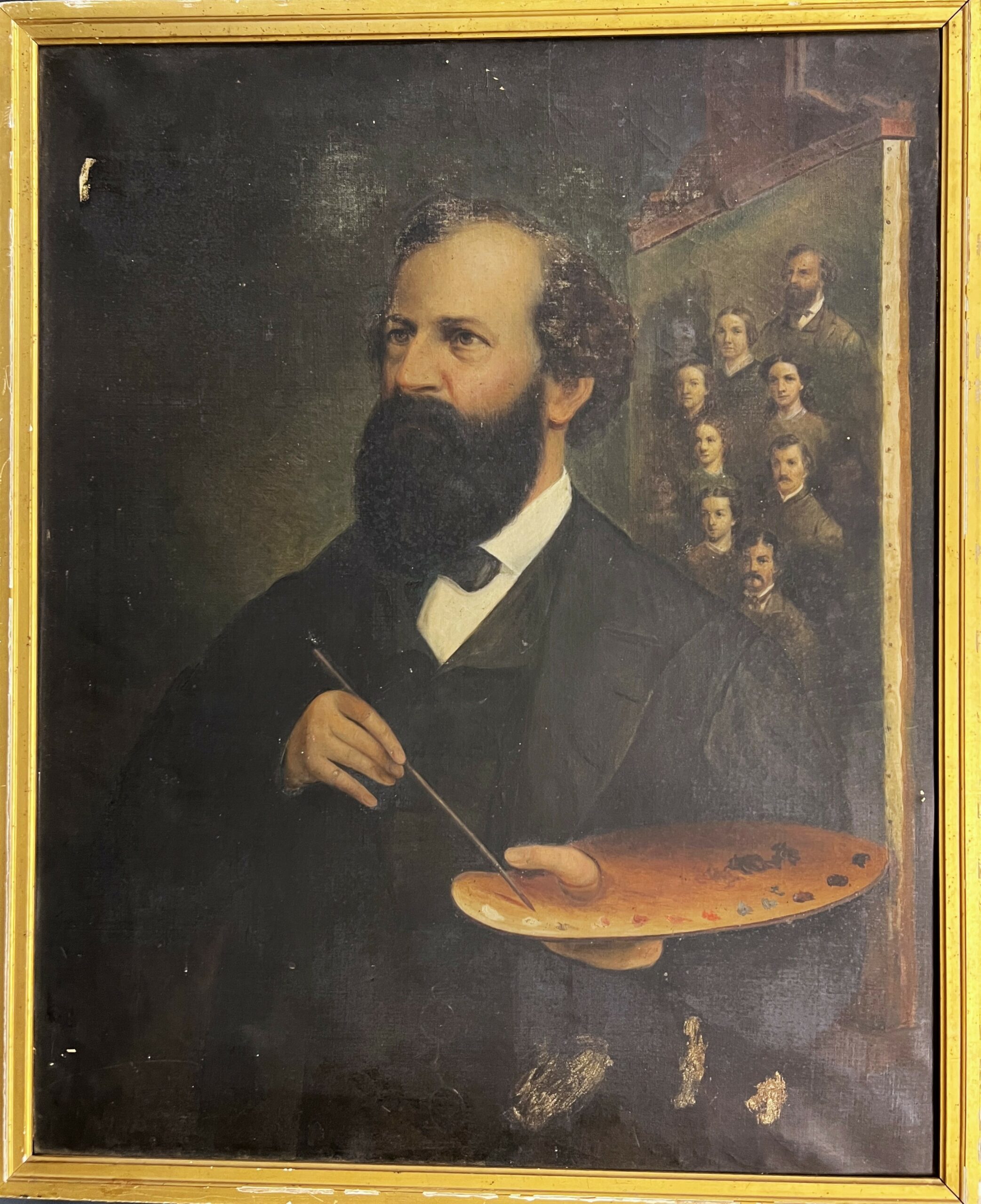

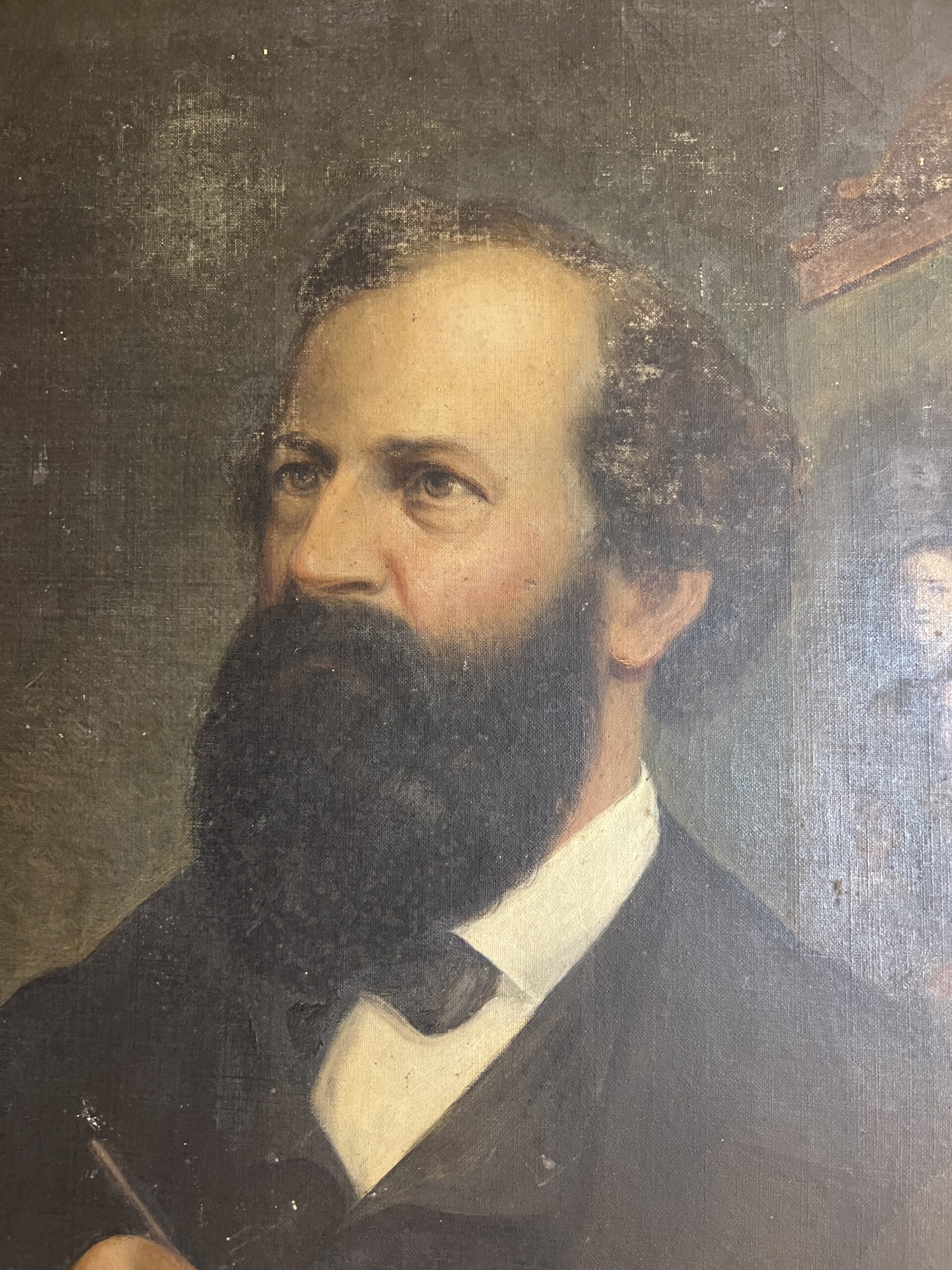

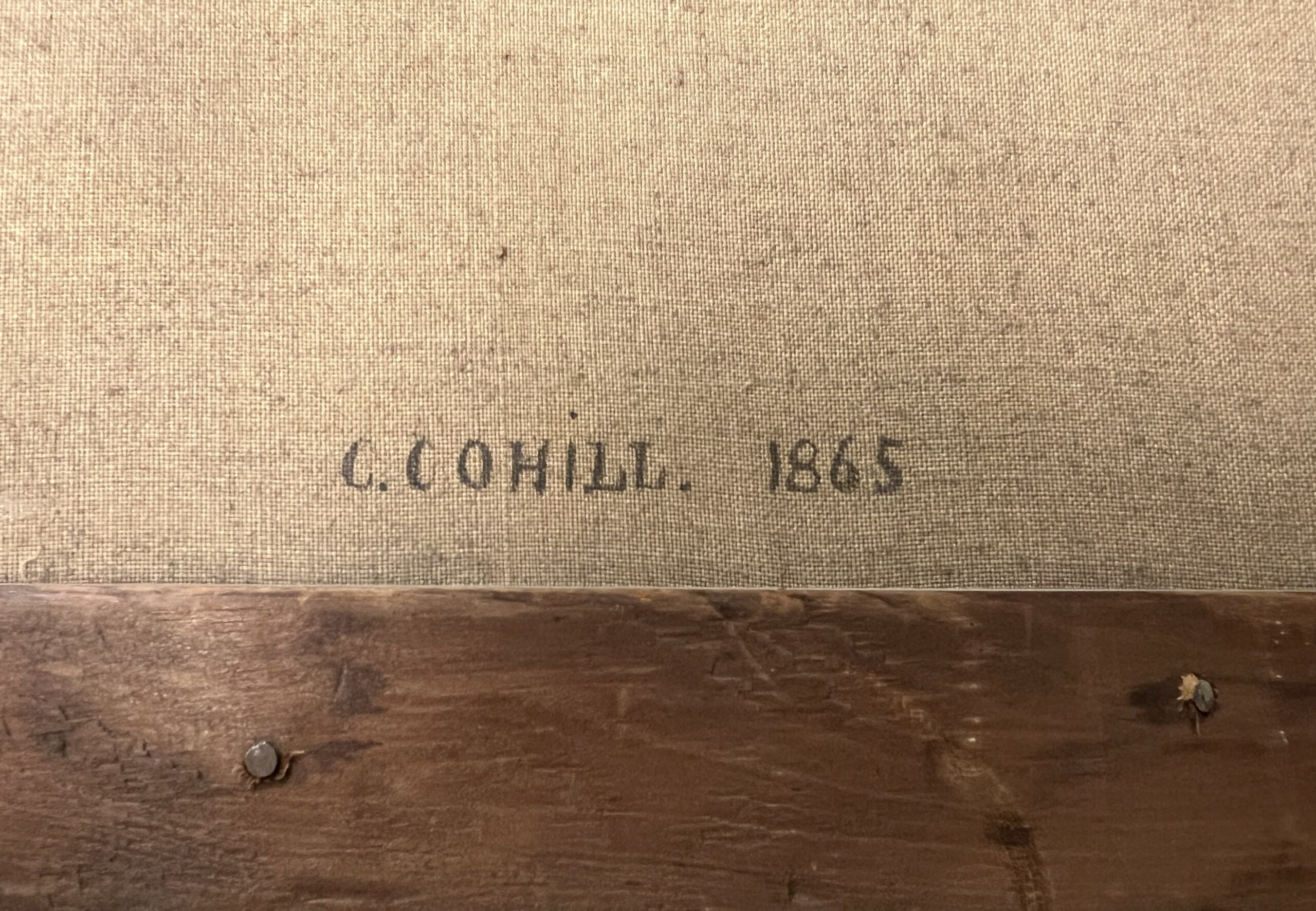

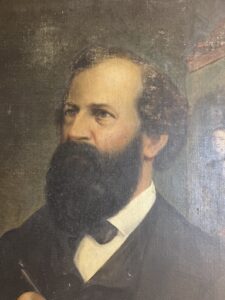

Self Portrait of Artist Charles Cohill, 1865. 82.33.2

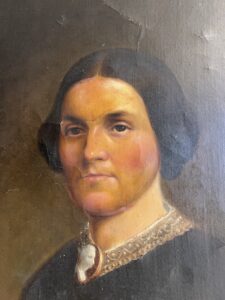

Portrait of the artist’s wife, Ann Cohill, 1865. 82.33.1

Portrait artist Charles Cohill was born in Pennsylvania in 1810. He married Ann McCormick on February 17, 1833, in Philadelphia and they had at least eight children, six of whom lived to adulthood. In this self-portrait from 1865 Charles painted himself, the artist, painting his family on a canvas set up on an easel. At the top of the portrait, he painted himself and his wife Ann. He appears to be wearing the same clothes he wears while painting and he faces in the same direction. His children appear below them, most likely in order by age left to right, top to bottom, and represent Caroline, Ann, Mary, Charles Francis “Frank”, Emma, and Harry. If you look closely near the top and bottom of the left-hand side of the canvas, he is painting what appears to be two infant faces that have been blurred to appear almost as ghostly images which most likely represent the infant daughter and infant son that the couple lost.

Charles and Ann lived in Philadelphia their entire lives. Ann died on March 9, 1891, and he passed away just twenty days later on March 29. In the will Charles drafted in between his wife’s death and his own he left all his art supplies, sketches, and books on art, including one of his most valuable possessions a book on art written in 1695, to his “beloved grandson Harry Harris” who was also an artist. In Charles Cohill’s will he states that he would like to be buried in his family plot in Monument Cemetery with a headstone installed and “upon this stone shall be inscribed the dates of the births and deaths of those who have gone before us.”1 Sadly, Monument Cemetery was sold in the 1950’s to make way for Trinity University’s athletic fields. The bodies of more than 28,000 souls, including Charles and his family, were reinterred in mass graves in Lawnview Cemetery. Only 300 headstones were saved. The rest were used to shore up the Delaware river banks, and some can still be seen when the tide is low.2

In the time before photography, portraiture was the only way to save the likeness of a person, and as mortality rates were so high during that time, portraits served as important pieces of remembrance for loved ones. Portrait artists could be found in cities large and small. “Portraiture was the dominant form of American painting in the 18th century and the first half of the 19th century.”3 Originally portraits were painted for the wealthy and having their portraits painted showed a symbol of your high status. This changed with the onset of the industrial revolution. A rising middle class and growing business population wanted equal access to material goods. “This new rank of Americans used the portrait to express their pride in societal and economic accomplishments and their likenesses became a reflection of their own self-image.”4 The demand for quality portraits when Cohill was in business would have been high.

Painters would usually study under an established and, if possible, well-known artist. It is purported that Cohill studied under John Nagle (1796-1865), a fellow Philadelphian and important American artist. Although Cohill would have undoubtedly sought out commissions, it was also common to paint portraits of popular people of the time, even those they had never met. One of the first mentions of Charles Cohill comes in 1841 when a Philadelphia news article gave a good review of a portrait of his hanging in a hotel, that of President William McKinley. He was said to be, “a young artist who bids fair to rank among the most conspicuous in his pursuit.”5 Painting the famous was a way to get their name out there. Articles in later years suggest he made enough of a name for himself that he also took many commissions.

In later documents, after around 1860, Cohill began listing his occupation as “artist” instead of “portrait painter.” Photography had come onto the scene. Cohill opened his studio on the popular Chestnut Street which bustled with shops of all kinds. He advertised himself as selling both “ambrotypes and photographs, the best in the world.”6 Cohill also found another avenue of income from photography. Two articles mention prisoners being marched from their cells to his shop for him to take their likenesses for identification. He was the only person to photograph the mass murderer Anton Probst who brutally murdered seven members of the Dearing family and their young stable hand.7 After Probst was charged and hanged Cohill took advantage of the fact and advertised that “a true likeness of the murderer of the Dearing family can be seen and copies for sale.”8 Like many painters Cohill embraced this new medium of photography either by his interest in it, or out of necessity, and found profit in it. He never removed the title of artist from his name as, like many other portrait painters, he found photography to simply be another form of portrait art.

Miscellaneous photographs Charles Cohill took in his studio can be found for sale on the internet, but more importantly many of the portraits he painted can be found as well. I have found at least ten portraits painted by him, some of well-known people such as Queen Victoria and military men, and some that are unidentified and seem to be simply ordinary people. The Philadelphia Academy of Fine Arts owns one and the New-York Historical Society has two. Undoubtably there are more. Although the monument he asked for in his will no longer stands, his work certainly does and this portrait in the GCV&M collections serves as a remembrance of him and his family.9

- www.ancestry.com ↩︎

- Katrina Ohstrom, “Watery Graves,” Hidden City Philadelphia, September 10, 2019, https://hiddencityphila.org/2011/09/watery-graves/. ↩︎

- Laura Pass Barry, “Artists on the Move: Portraits for a New Nation by Laura Pass Barry,” InCollect, March 8, 2018, https://www.incollect.com/articles/artists-on-the-move-portraits-for-a-new-nation ↩︎

- Laura Pass Barry, “Artists on the Move.” ↩︎

- Newspapers.com. Public Ledger, May 21, 1841. https://www.newspapers.com/article/public-ledger/144464462/. ↩︎

- Newspapers.com. Public Ledger, September 1, 1860. https://www.newspapers.com/article/public-ledger/144464400/. ↩︎

- For information about Probst and the Dearing family see: https://www.newspapers.com/image/168110693/. ↩︎

- Newspapers.com. The Philadelphia Inquirer, April 14, 1866. https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-philadelphia-inquirer/144464604/. ↩︎

- The GCV&M has many portraits in its collections. MacKay House is filled with the portraits of the family and Foster House has portraits of the Brown family from the mid 1830’s. ↩︎