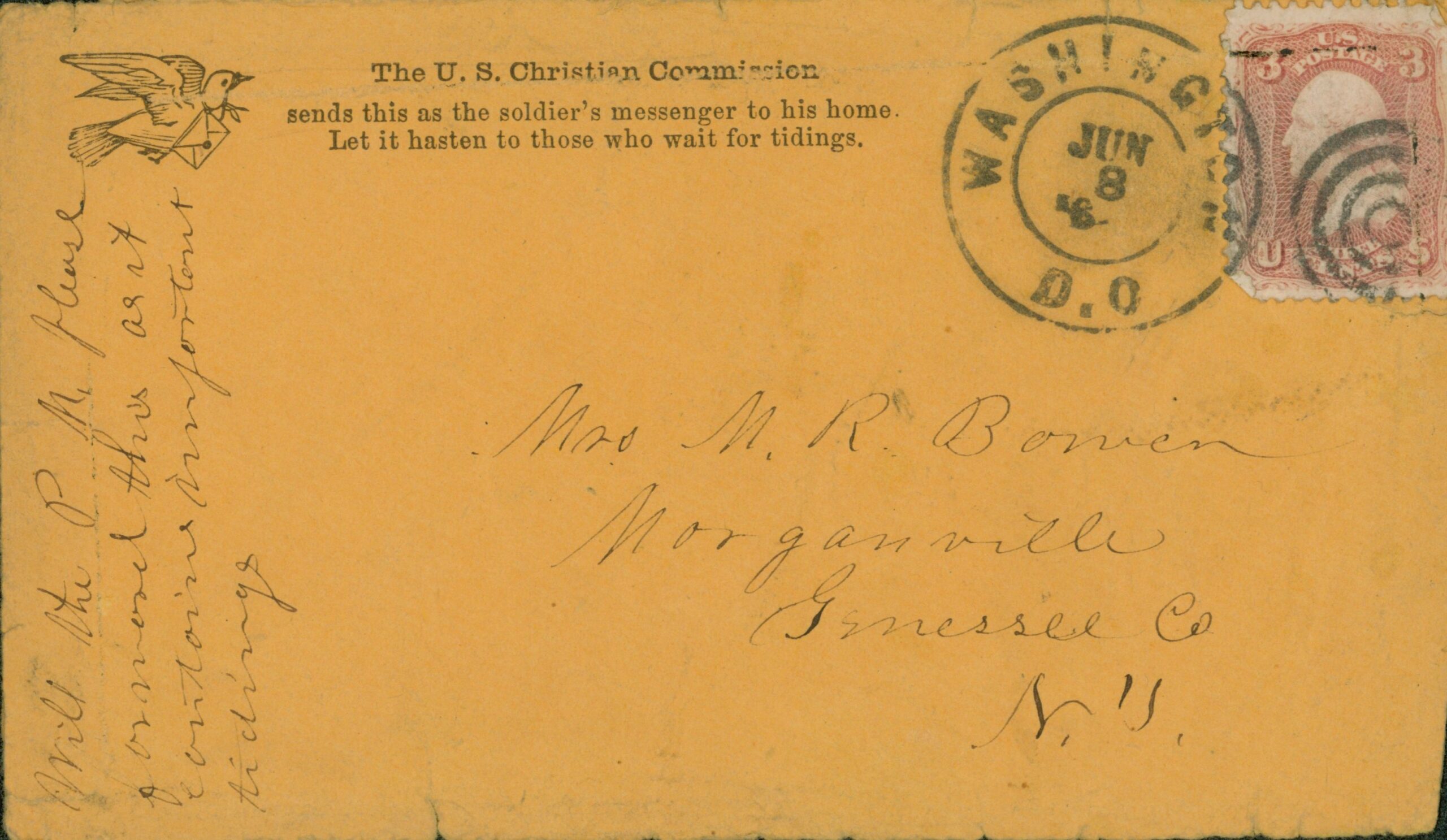

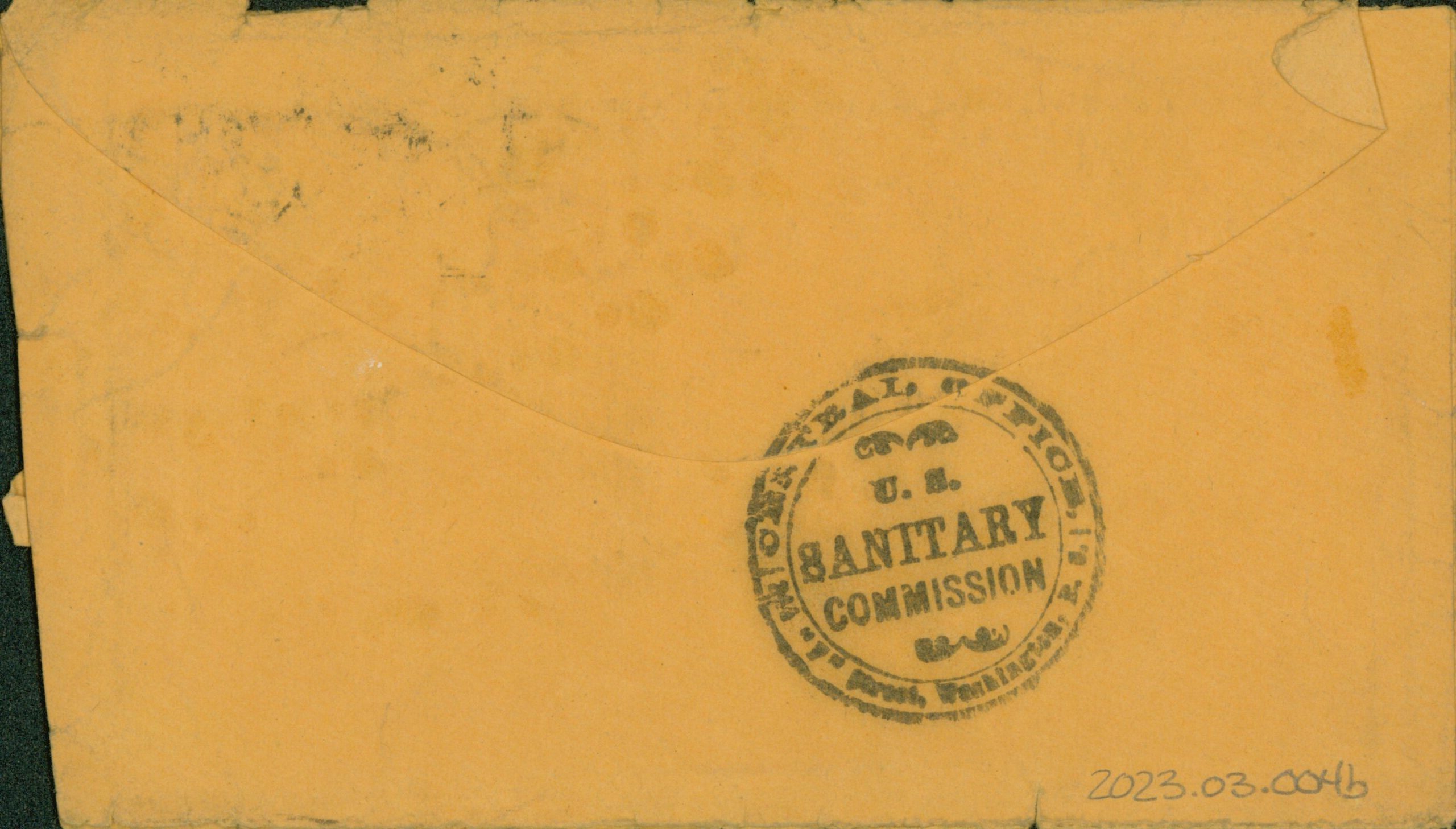

Civil War Death Notice, 1864. 2023.03.004a-b

(Collection 2023.03)

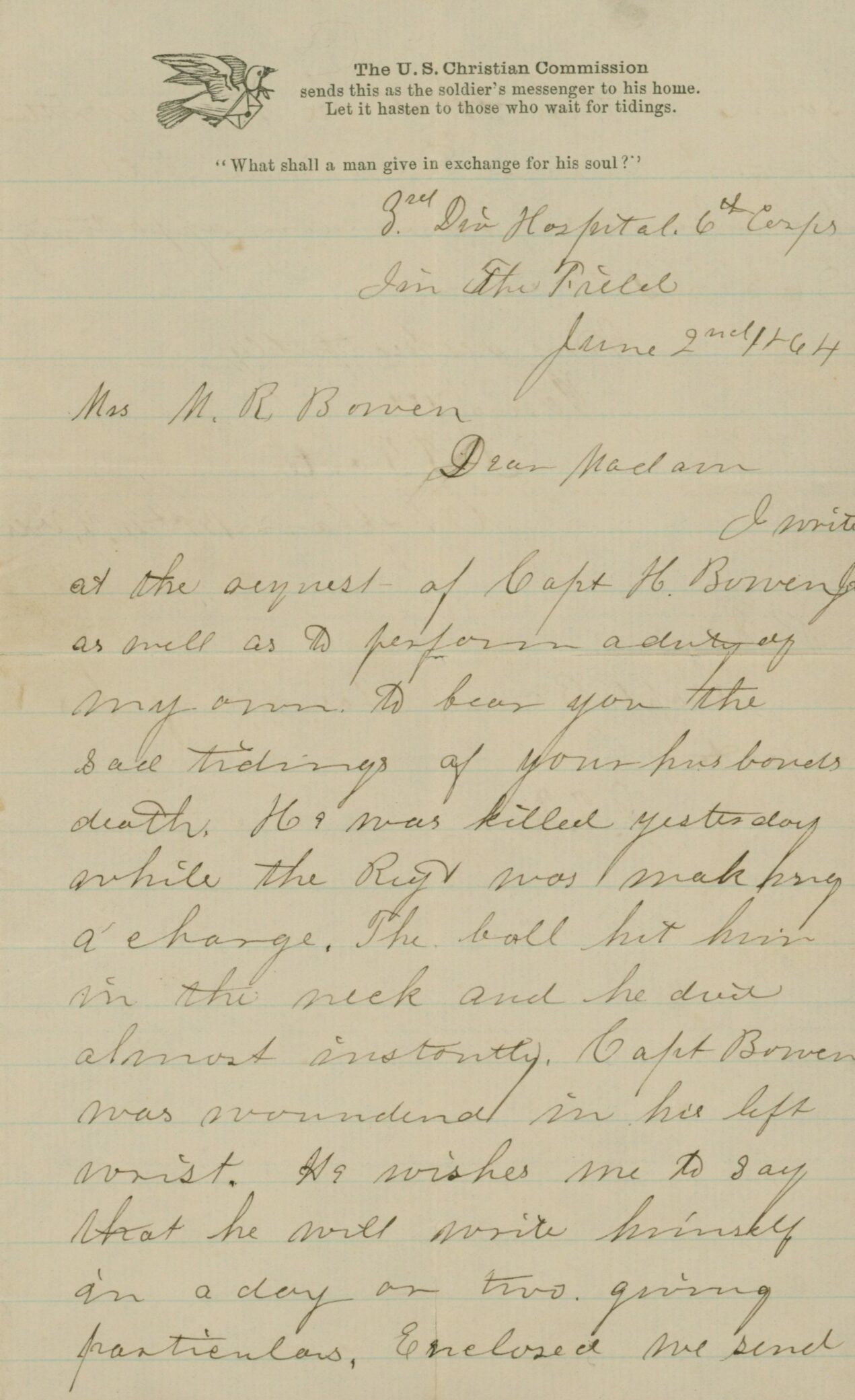

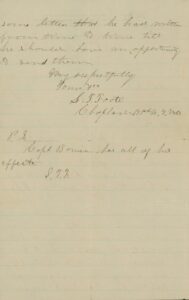

The letter reads as follows:

[front] “I write at the request of Capt H. Bowen Jr as well as to perform a duty of my own to bear you the sad tidings of your husbands death. He was killed yesterday while the Reg’t was making a charge. The ball hit him in the neck and he was killed almost instantly. Capt Bowen was wounded in his left wrist, He wishes me to say that he will write himself in a day or two, giving particulars. Enclosed we send [back] some letters that he had written from time to time till he should have an opportunity to send them.

Very Respectfully, Yours [?]

S.T. Foote

Chaplain 151st N. Y. Res

P.S. Capt Bowen has all of his effects. S.T.F.

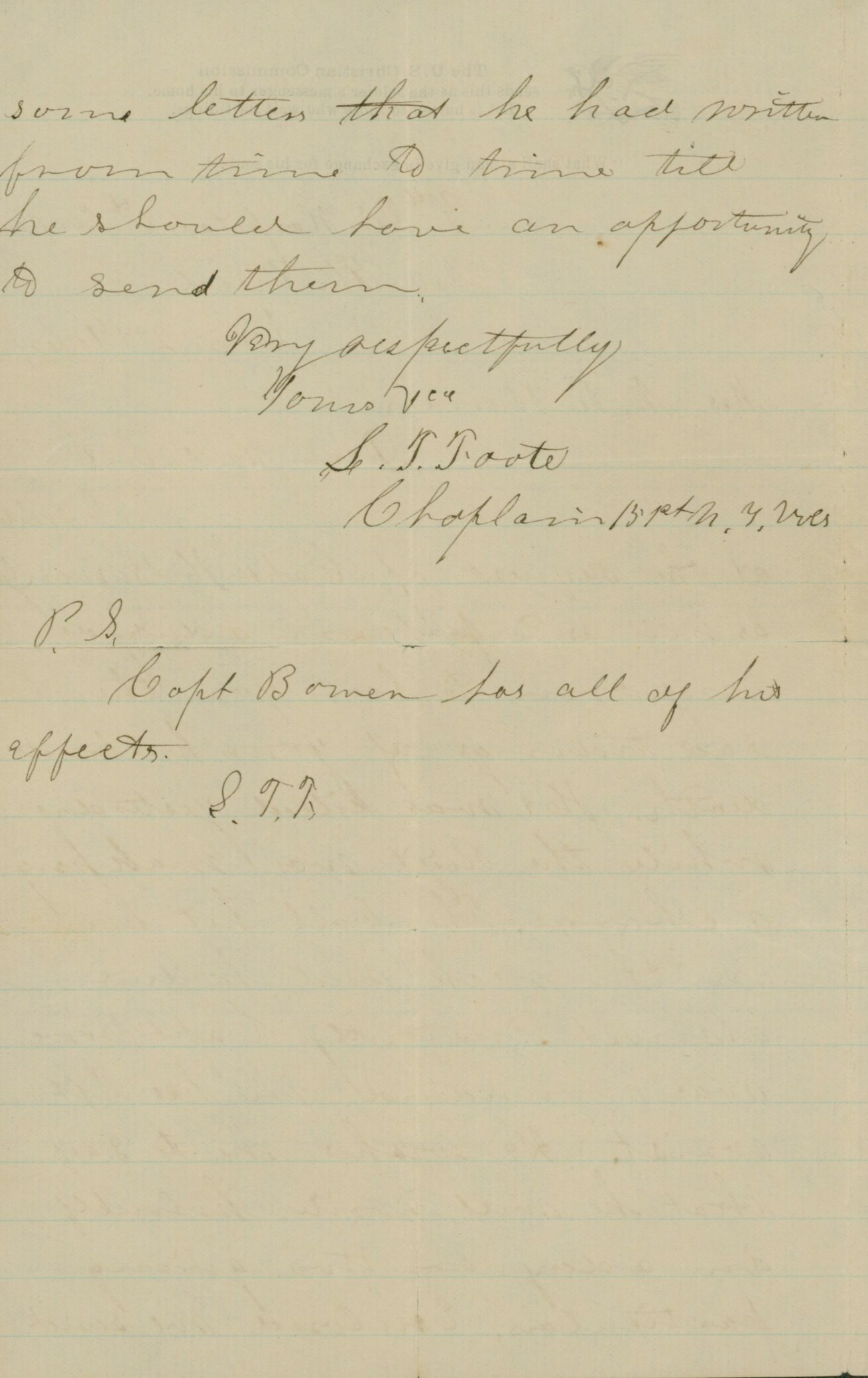

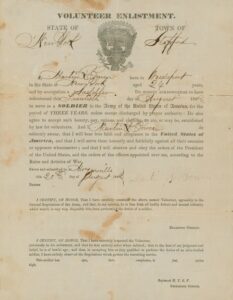

This letter was sent to Harriet Booth Bowen, wife of Martin Bowen. Martin Remington Bowen was born in Weedsport, New York, in 1837 to Anson Bowen and Almira Remington and he married Harriet L. Booth in 1862. Harriet was born in Stafford, New York, in 1840, the daughter of Hezekiah Booth and Eliza Shedd. After marriage the couple settled in Stafford where many of Harriet’s family members lived. On August 20, 1862, at the age of twenty-four Martin left his new bride at home and volunteered to fight for the Union army during the Civil War. He joined the newly formed 151st New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment, Company A, in which the Commander was Hezekiah Bowen. Hezekiah was Martin’s second cousin on the Bowen side, Hezekiah’s wife being Martin’s mother’s sister. This is the Captain Bowen mentioned in the death notice. The 151st was comprised of men from small towns in Western New York. It was not uncommon for a soldier to have family members and friends with him, and there were many connections in the 151st as the soldiers came from the same region. A large contingency of Company A was made up of the sons of prosperous farmers. Helena Howell, a young relative of Martin and Hezekiah wrote, “it was composed of American born boys, having had good advantages and education, mostly sons of well to do farmers. It was dubbed the ‘top buggy company’ in view of so many being able to take young ladies out in top-buggies.”1

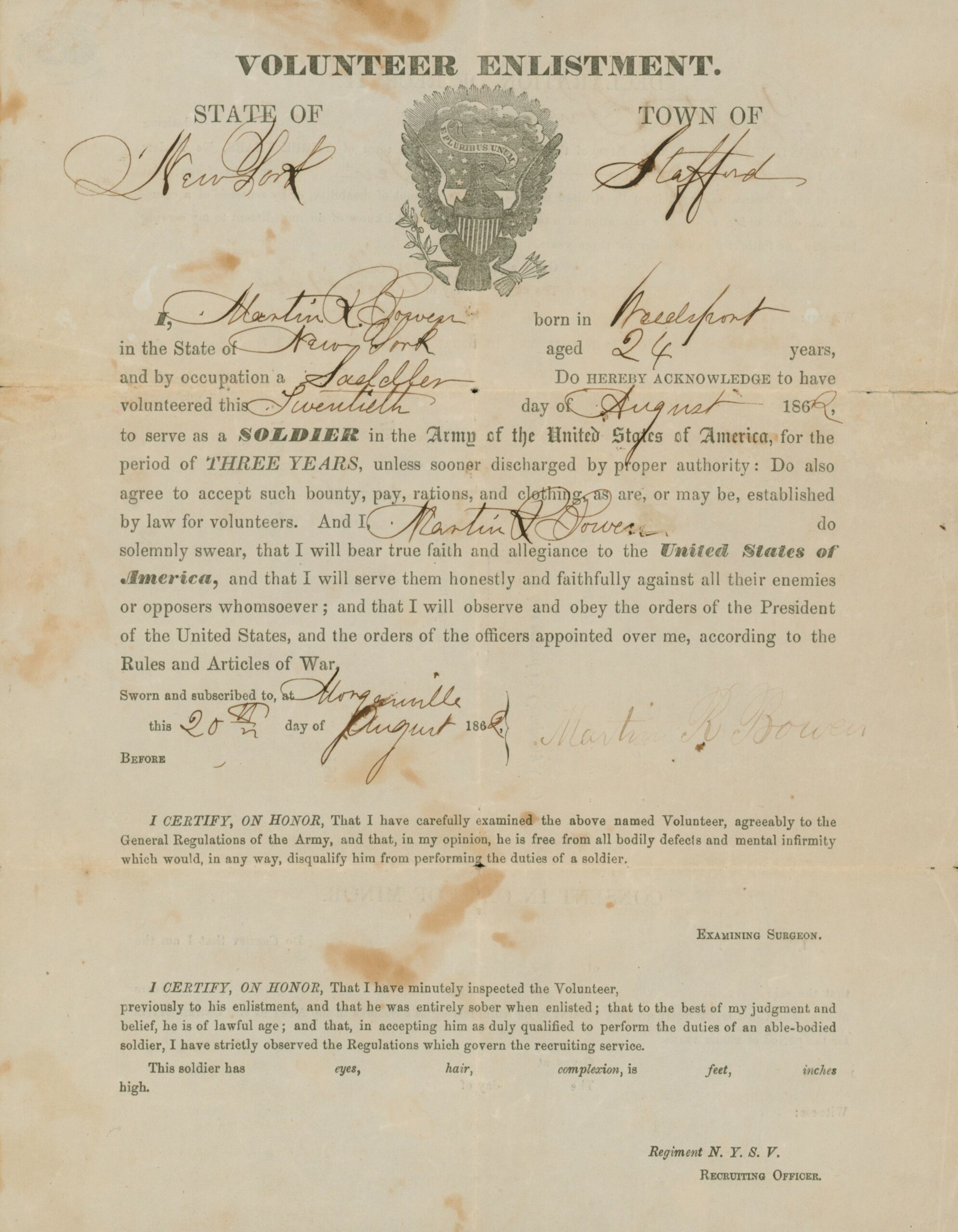

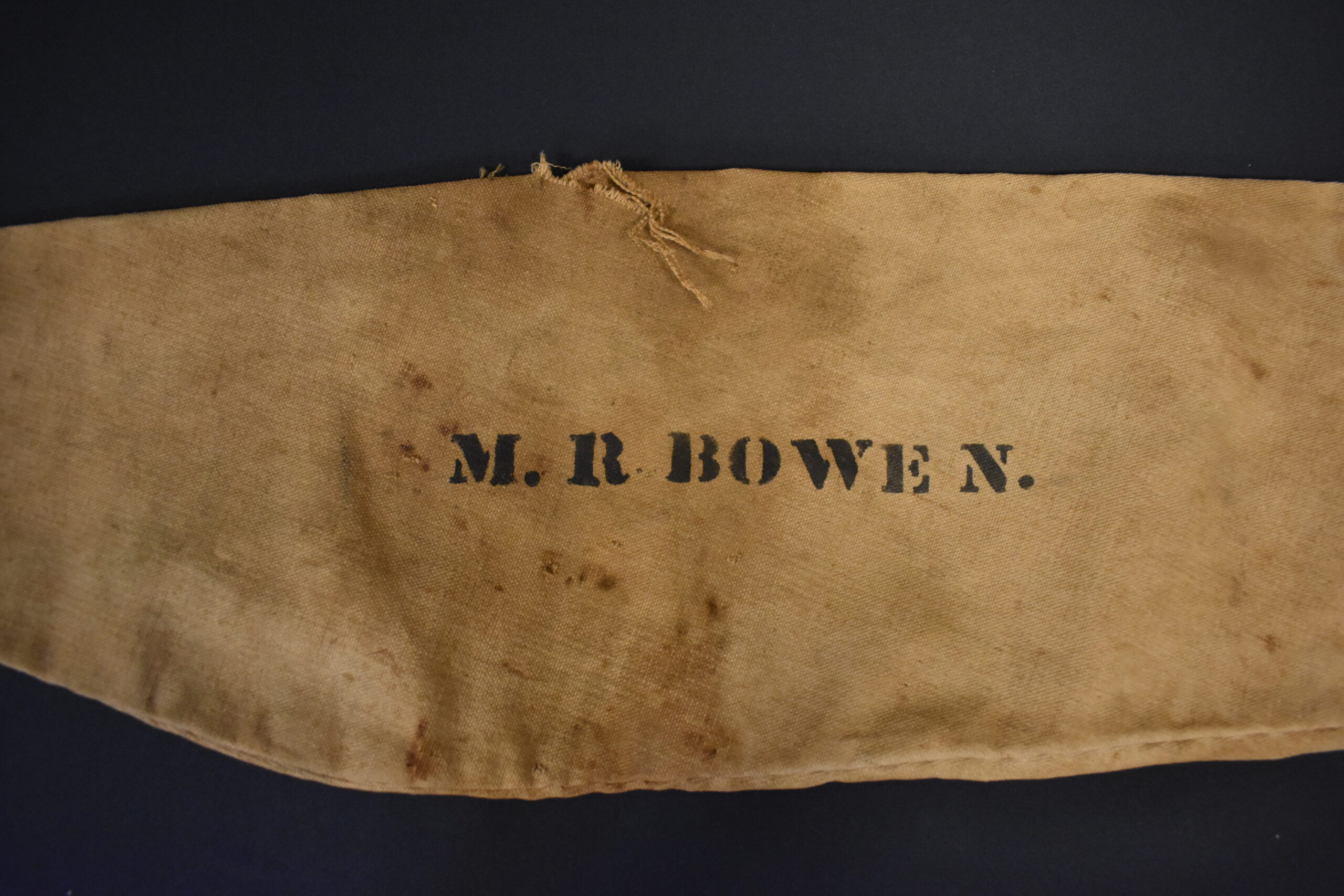

Each soldier in the Company was responsible for purchasing their own firearm. “After all the discussion, each member of the company bought his own Sharps rifle, paying $40.00 for it. These rifles were to make them the best equipped company in the Regiment.”2 This is the rifle that Martin would carry with him and after his death it was returned to his widow, most likely delivered by Hezekiah Bowen as he had possession of his effects. That rifle, belonging to Martin, a .52 caliber Sharps rifle, and its personalized cover, are also part of the GCV&M collection. Martin would serve for two years before his death.

In the Spring of 1864, the 151st marched southeast through Virginia and engaged in battles in Wilderness, Spottsylvania, North Anna, and Totopotomy.3 Continuing that trajectory, they reached Cold Harbor, Virginia, after being on the move for more than 16 hours. The goal was to get to Richmond. It turned into a bloody battle, the worst being on June 3rd when over 7,000 Union troops were killed in just 20 minutes. Martin Remington Bowen would not be going home. His wife Harriet was left a widow. They did not have children, she remained near her hometown of Stafford never remarrying, and she outlived him by almost 50 years. Martin’s rifle, the death notice, and his enrollment papers were passed on through the Booth family via Harriet’s sister’s family. Martin’s great-great-nephew, Jeffery Waterman donated these items to the GCV&M in 2023. One hundred and sixty years after Martin fell on the battlefield at Cold Harbor his story can still be told, and his sacrifice will not be forgotten.

In our present lives we can all imagine, and many of us have experienced, the constant worry about a family member in the military. In addition to that universal worry the wives of Civil War soldiers had many other obstacles to overcome. Economic status, race, family support, and geography made a difference in what those left behind experienced. Families in Western New York had the comfort of being far from the battlefield and many had family close by to help support them. Harriet stayed with family members both during the war and after Martin was killed. Many in the Southern United States had a different experience. John F. Brost, a soldier for the Union army wrote, “The people up north do not know what war is. If they were to come down here once, they would soon find out the horror of war. Wherever the army goes, they leave nothing behind them, take all the horses, all the cattle, hogs, sheep, chickens, corn and in fact, everything, the longer the rebs hold out the worse it is for them.”4

Starvation and homelessness were rampant in the South but not limited to that geography. Families in both the North and the South who had depended on men who were now at war were missing the income they brought in which caused a great hardship and led to a fear of destitution. Many women took on jobs to keep themselves and their families fed. Many farmers’ wives had to take on tasks they were not trained to do. Union soldier Frank “Bull” Paxton wrote his wife, “I do not have time to think of my business at home…do just as you please.” He goes on to say. “I hope you are having good success as a farmer, so, if I should be left behind when the war is over, you may be able to take care of yourself.” 5 Bull Paxton was one of the many who did not return from the war.

Maranda Davis, who lived in Mississippi and was left to farm and raise six small children during the war, wrote to her husband William,

“So you see I am going to fix for farming. I bought four bushel of oats & I want to sow them next week, if the weather is fit, I can’t tell you anything about the wheat for I am afraid to go out to look at it. The general opinion is that it froze out. If wheat falls this year, it looks like people will be ruined for corn is very scarce. William, Jo Baly wants the middle field & I want you to write to me & let me know whether I must let him have it or not. Give me all the advice about farming for you know I don’t know anything about it.”6

The situation was especially dire for both freed and enslaved women. Many of the men in their families were forcibly separated from them to provide labor for the war. Many women were able to escape enslavement, but many others did not have the means or knowledge of how to do so, and many more were recaptured. They too struggled with caring for their children with a war in their backyard. Some were able to find work of some kind but regardless of whether they had been freed or if they were still enslaved their rights were restricted just as before. “Black women, both enslaved and free, held positions subordinate to white women and generally performed the more unpleasant and physically demanding tasks.”7 Women who looked for work at the army camps faced the threat of assault. “[Enslaved] Women also continued to face the risk of both physical and sexual violence from white soldiers in camps. Some women’s immediate escape from slavery, then, was painfully difficult.”8

Through the war women stepped up and did what needed to be done to give them and their children the best chance at survival. But it did not stop there. By the war’s end there were around 670,000 casualties. Husbands, sons, fathers, and brothers. The entire country was left with widows, orphans, and heartbroken families. “The people, the lives they lived, and the era are all gone and no historical account or piece of evidence, even when combined with all of the others, can ever recapture the past…a primary goal … then, should be creating experiences and telling stories”9 By using these artifacts the stories of the women left behind can be told. The story of Martin and Harriet can be used to help bridge the gap between the past and the present.

- Paul Stephen Beaudry, The Forgotten Regiment: History of the 151st New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment (Cleveland, Ohio: InChem Pub., 1995). ↩︎

- Beaudry, 14. ↩︎

- Civil War Index – 151st New York Infantry, 2010, https://civilwarindex.com/armyny/151st_ny_infantry.html. ↩︎

- Juanita Leisch, An Introduction to Civil War Civilians (Gettysburg, Pennsylvania: Thomas Publications, 1994). ↩︎

- Leisch, 59. ↩︎

- Maranda Davis to William Anderson Davis, “Miranda Davis’ Letter to William Anderson Davis,” MsGenWeb Project, 2012, https://www.msgw.org/tate/letter.htm#Davis. ↩︎

- Aerika A. Wright, “Women During the Civil War,” web log, Encyclopedia Virginia (blog), 2020, https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/women-during-the-civil-war/. ↩︎

- Emily West and Sian David, “Enslaved Women in the Civil War,” Hidden Voices: Enslaved Women in the Lowcountry and U.S. South, 2020, https://ldhi.library.cofc.edu/exhibits/show/hidden-voices/continuities-and-changes/enslaved-women-in-the-civilwar. ↩︎

- Jessica Foy Donnelly, Interpreting Historic House Museums (Walnut Creek, California: AltaMira Press, 2002). ↩︎